It’s easy being green. But blue, yellow and red? That’s another matter.

Special education students are learning to express how they feel and to identify others’ emotions through a curriculum that helps develop social skills. High school junior Heather Arney knows if she’s not in the “green zone,” where she’s happy and ready to learn, it’s time to take a walk, ride her bike or sit down for a while. “I feel OK in the green zone,” she said.

In her moderate cognitively impaired class, Heather and her peers use language from the district’s Social Thinking curriculum. The program provides tools for students who struggle to naturally learn social skills, and for all students – beginning in kindergarten – to develop strong skills and words for social interaction.

For most people, social skills develop naturally and become intuitive. But for some, including people with autism, that’s not the case. Yet skills, including expected behavior when people share spaces, communicate and interact, can be taught.

Around teacher Courtney Redmond’s room, visual aids, like happy and angry faces, help students identify nuances of social communication and interaction. Redmond, who teaches several autistic students, said it’s important for students to think about what a frown, smile or uncomfortable face means, how to respond to it, and to know how to cope with frustrations, anxiety and other emotions.

“They have a hard time with emotional regulation and identifying how other people are feeling and how they are feeling,” she said.

The class also focuses on “expected and unexpected behaviors,” and students have learned to tell each other when behavior is not what they expected. That helps fit into teaching about peer relationships, sexual education and health, Redmond said. Students learn about personal space, how certain behaviors make people uncomfortable, and appropriate and inappropriate touches.

Other focus areas include perspective-thinking and big versus little problems.

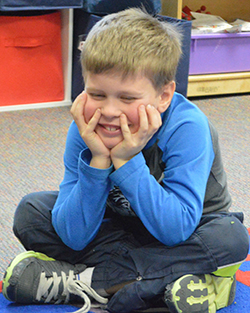

“I’m in the green zone. I’m happy and excited,” said senior Ruthie Roelse, who has Down syndrome, during an activity when students shared how they were feeling for the day. That led into a “zone regulation” matching game.

Students identified emotions that would result from experiencing different situations. Your pet is missing? You’re in the blue zone. You’re asked to stop or put away something that you enjoy doing? You’re in the yellow zone. If you find yourself in the red zone, when you’re about to explode with anger, it’s time to use de-escalation skills to “get back to green.”

All Students Can Benefit

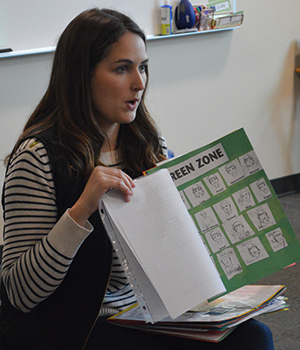

To varying degrees, everyone can benefit from being taught social skills, said Katee Aubil, speech language pathologist at Emmons Lake Elementary, Kraft Meadows Middle School and Caledonia High School. The elementary-level Social Thinking curriculum is used in general education elementary classes at Emmons Lake.

“This curriculum develops lifelong abilities of how you think about others, how you think about your own thoughts, and how those interact with people,” Aubil said. “That translates to every social situation.”

But it’s often an area skipped over by standard curriculum. “Through research we’ve learned that if we’ve never been taught or we don’t know how to interpret or own feelings or thoughts, or how to express those with others, that’s where those social breakdowns happen. It’s even in adulthood,” Aubil said.

Providing a common language for everyone to express themselves is a key part of the program.

“Being able to give students these tools of how they can ask for help, interact with friends and express their own thoughts and feelings, that’s only going to help you succeed more in school,” Aubil said.

During a social-thinking lesson in teacher Melissa VanGessel’s Emmons Lake kindergarten classroom, students used the elementary-level one-to-five scale to describe their mood, with one being happy and five angry.

“What if you forgot your backpack on the bus?” asked Aubil, who leads Social Thinking sessions in the class, which includes a few students with auditory processing difficulties. Students took the scale to a whole new level: “I think I’d be at a 5!” “I think I’d be at an 18!” “I’d be at a 1,000!”

Learning social interactions, “to give and take and problem-solve,” is a huge part of elementary school, VanGessel said. “This needs to be in our curriculum just as much as reading, writing and math.”

In a circle, students practiced “getting back to a one,” rubbing their legs, squeezing their hands together under their desks and taking deep breaths. They then practiced expected and unexpected behaviors, and following a group plan.

While passing a bean bag from student to student, VanGessel instead put it in her pocket and said she wanted to keep it. Kindergartners, giggling at their teacher’s unexpected move, knew just what to say.

“Mrs. VanGessel, can you please follow the group plan?”

CONNECT

Grant Brings Sex Ed Instruction to Students with Special Needs