AJ gets up well before dawn to get ready for school and catch the city bus at 6:10 a.m. on a busy street outside of the motel where she lives. Half an hour later, she hops off to catch another bus a few miles away and makes it to her Kent County suburban school at 7:05 a.m.

At 7:30 a.m. the bell rings to begin first hour.

“When it starts snowing, I am going to have to get up earlier to get to school on time,” said the high school junior, who appears younger than her age. Her thick, dark hair is in a ponytail and her deep brown eyes widen as she talks.

AJ, who wishes to remain anonymous, will catch the bus again at 3 p.m. for the hour ride back to the motel. She tries to already have her schoolwork done by the time she arrives home. “Some of my homework, I can’t do at home. There’s no Internet connection. I try to get everything done in school.”

She keeps on top of homework and studying as much as she can, sometimes meeting with school counselors, and often skipping lunch. Once she gets back to the motel, she cares for her 10- and 11-year-old sister and brother to help out her mother, who has to leave for work.

“They do their homework. I give them popcorn, oranges and apples. They watch TV. I cook dinner around 5 p.m. I make sure everyone’s got food.”

Academics, Attendance and Mental Health

AJ and her siblings are among nearly 2,500 students that qualify as homeless in Kent County schools. It’s a number that has steadily increased as housing costs have risen and only 4 percent of rental units are available. Families without enough money on hand for first month’s rent and a security deposit, or who have poor credit or an eviction history, end up with nowhere to go but to double up with others, or live in shelters, motels or vehicles. Even shelters have waiting lists.

Along with struggling to meet basic needs, the trauma of homelessness impacts students’ academics, attendance and mental health, said Casey Gordon, who coordinates the McKinney-Vento Act grant for Kent and Allegan counties at Kent ISD. The act is federal legislation that helps children continue to go to school even if they don’t have a permanent home.

Uncertainty caused by losing housing and not knowing where to go next can be excruciating, Gordon said.

“It’s really difficult to learn if you are thinking about, ‘Where am I going to go?’ ‘Am I going to be safe?’ or ‘I just lost all of my stuff,’” she said. “There are so many things going on when you don’t have a safe place to come back to every night.”

According to a University of Michigan analysis, Michigan has one of the largest populations of homeless students in the United States. In

school year 2015-16, Michigan ranked 6th among states for the most homeless students. By comparison, Michigan ranked 10th for overall student enrollment.

In 2018/2019, the most recent figures available, Grand Rapids Public Schools reported the most homeless students in the state, with 984 students. That was followed by 873 in Kalamazoo Public Schools, 602 in Detroit Public Schools and 497 in Lansing Public Schools, according to Michigan Department of Education data.

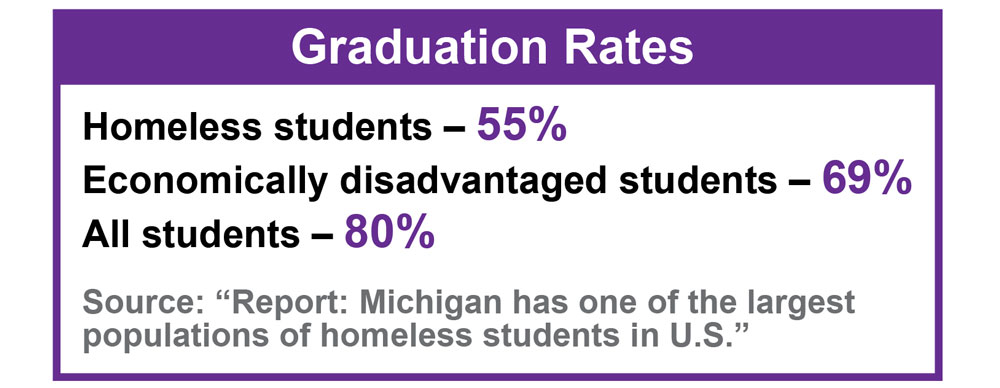

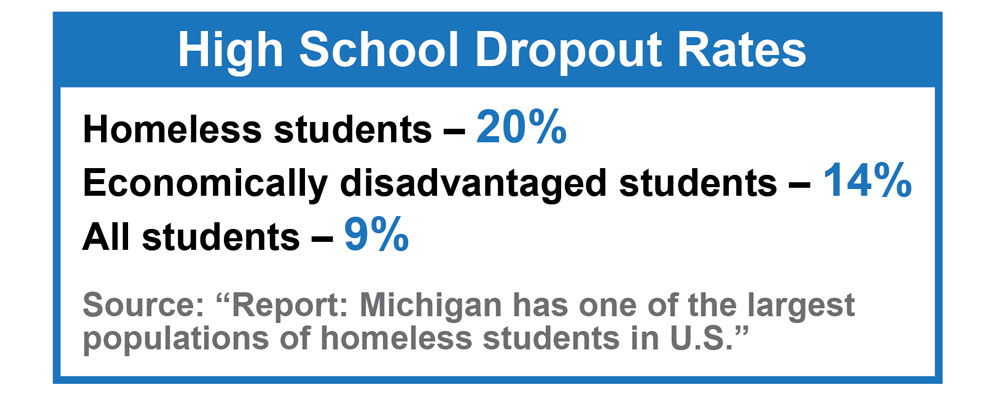

Housing instability has broad impacts on student performance. According to the U-M report, homeless students in the class of 2017 had the lowest four-year graduation rate of any group in Michigan for which data was available.

Homeless students also had the highest high school dropout rate of any group in Michigan that year, with one in five homeless students, or 20 percent, leaving high school early.

Impacts of dropping out can be lifelong. According to information from mischooldata.com, the median annual wages in Michigan for a worker with no high school diploma after five years in the workforce is $13,400, compared to $22,100 for a high school graduate. (Those with an associate degree earn $39,700; a bachelor’s degree, $50,000; and a master’s or higher, $68,500.)

Stress and Struggles

Kent County schools have staff members working to support homeless students and families. They see the day-to-day struggles students face.

Jessica Tornow, Kent School Services coordinator for East Kentwood High School, does all she can to remove barriers for students, so they can best learn in the classroom.

“There are things they are dealing with on the outside that affect their ability to be successful at school,” Tornow said. “It’s hard to be here and understand the bigger picture of what they need to be learning in the classroom that could affect their future, while they are still thinking about ‘Where might I sleep tonight? Is there going to be water? Is there going to be food on the table?’ Those might seem extreme, but it’s the reality of some of our students.”

At a high school level, the stress often comes with a huge sense of responsibility to help provide for their families.

“There are the stressors of ‘I need to go to work. I need to provide for my family, while getting all my school work done.’”

Sarai Gamez, KSNN community school coordinator for Parkview Elementary School in Wyoming Public Schools, sees the anxiety students face at the elementary level.

“It’s hard for them to just sit in class,” Gamez said. “We have trouble with a

lot of them wanting to leave class. It’s understandable that they can’t focus

on their school work if they have all these things in their head.”

Attendance is a major issue. According to mischooldata.org, 50.3 percent of homeless students in Kent County were chronically absent — missing 10 percent or more days of school — in 2018-2019. Of students who weren’t homeless, 13.7 percent were chronically absent.

“Most of the families I’ve seen, one day they are here, one day they are not,” Gamez said. “They are late to school, which is understandable because sometimes there isn’t transportation or they are coming from out of district.

“Attendance is super important for any school and any student, so when they are missing even 30 to 45 minutes of the day, they are already falling behind — which then adds up to that anxiety they have or stress going on in their lives.”

Small Room, Big Hopes

AJ has lived with her family in the motel — a place where semi-permanent residency is common — since the beginning of the school year. The rate for a room with a kitchenette is $335 a week.

“It’s a little bit bigger than this room,” she said, referring to the high school counselor’s office where she shared her story. “There’s one big bed and me and my mom and sister sleep there, and my brother sleeps on a pallet on the floor.”

There’s little money left for food, AJ said. “We got this month’s food stamps, but they sent a letter saying our food stamps are cut off. They cut off people’s food stamps– it’s like a regular thing — thinking they just sell them, but we are not. We actually do need them.”

For clothes, they go to the district’s giving closet. “We look for clothes for my siblings. I just focus on them. I can’t really focus on myself. I feel too greedy.

“My mom’s plan is to wait until she gets taxes back,” she continued. “She is going to find an apartment or trailer home to live in.”

AJ knows what she’s up against when it comes to the challenge of being homeless. “Not a lot of people are going to get out of this group,” she said. “Not many people are strong enough.”

But AJ is a good student, earning A’s and B’s. She loves forensic science, social studies and English. She hopes to be a teacher or forensic scientist someday. Northern Michigan University or Grand Valley State University are her top college choices. She has begun talking to teachers about recommendations for college. As of mid-December she had only been tardy once.

“Sometimes I don’t see my progress. I only see the bad,” AJ said. “I feel like I’m not doing enough. If I could give myself that one extra little push, you know?”

Her sister and brother are also good students. She talks positively about them and how they handle their situation.

“All of us do well in school. My sister, she’s the happiest person. … My brother, he understands some things. Me, I tend not to be treated as a kid. I understand a lot of things.”

But AJ puts into words the social impact of being a homeless teenager, the isolation she feels.

“I never really let it show. I put on a happy smile, even if people don’t really know what I am going through.”

For now, AJ just focuses on what she has to do every day. She has constant anxiety and often can’t sleep. “If I’m stressing a lot, I don’t go to sleep until around 1or 2.”

Still, she dreams of a bright future.

“I honestly want to graduate from high school. I do want to go to college. If not, I will go to trade school.

“I want to be at a place where I am stable and I don’t have to go through the things I go through today.”

CONNECT

Overcoming homelessness to get her degree she’s ready to help others